Shooting the Mafia, Out of Focus

By Leonardo Goi

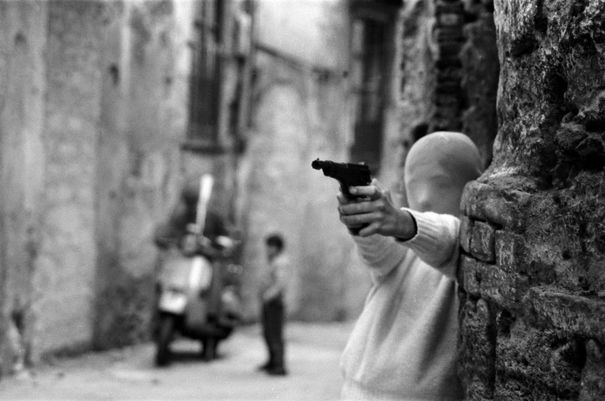

© Letizia Battaglia / Lunar Pictures

Sicilian photographer Letizia Battaglia began photographing Mafia murders on her home turf in the 1970s. Nearly fifty years later, she becomes the subject of Kim Longinotto’s Berlinale Panorama Dokumente entry, SHOOTING THE MAFIA. A largely engrossing portrait of a woman who confronted the Sicilian mob in a way few others dared to, Longinotto’s docu-biopic works best when it pivots on the ethical dilemmas surrounding how, and whether, acts of unspeakable violence should ever be portrayed. Where it stalls a little is when it focuses away from Battaglia’s own introspections, to embark on a far drier overview of Italy’s fight against the Mafia through the decades.

To be sure, Longinotto’s found a most fascinating subject. A preternaturally charismatic eighty-something with a rusty, smoker’s voice, Battaglia is graced with a magnetic stage presence that dons her musings a hypnotic aura. SHOOTING THE MAFIA is a genesis story, and Battaglia’s is one about and against a male-dominated industry that turns out to be just as cancerous as Sicily’s organised crime. Pitted against a deeply patriarchal society that sought to stunt her freedom, Battaglia looked to photography as escapism, and by the time Longinotto finally turns to the start of her protagonist’s career – a whopping 25 minutes into her documentary – SHOOTING THE MAFIA zeroes in on the contrasts between Battaglia’s humanist eye and the glamourized coverage the Sicilian mob had received from foreign media outlets.

It is here, in its excursion into the ethics of her photography, that Longinotto’s documentary offers some of its best material. Unmistakably aware of the moral concerns inherent to her work, there are moments when Battaglia reminisces about the photos she never took as “the ones that hurt the most.” Seesawing between a need to document the Mafia’s barbarities and a reticence to expose them in all their horror, Battaglia’s gruesome black and white portraits of corpses and crime scenes encapsulate the glance of a photographer at once fascinated and perturbed by her subjects. Indeed, there are moments when Battaglia’s reticence teems with awe for the bosses she photographed inside courts, “my hands shaking not out of fear, but for the emotion” of seeing Italy’s most wanted men stare at her camera with an insouciant smile.

Regretfully, Battaglia’s psychological introspection is a terrain Longinotto abandons way too soon. By its mid-point, SHOOTING THE MAFIA loses its biographical focus to embark on a far larger discussion of the impact of the Sicilian mob on the country’s development. The pivotal junctures of Italy’s battle against Cosa Nostra are all diligently flushed out (the barbaric assassinations of judges Falcone and Borsellino; the capture of bosses Totò Riina and Bernardo Provenzano), but the effect is to watch an engaging biography become a history lesson. As compelling a chapter in Italy’s recent history this may be, SHOOTING THE MAFIA’s second half is far less intimate and engrossing than the biopic the first had patched together.