Found Footage - Part I

The first part of a journey of discovery into the world of borrowed images - the act of collecting frames out of control can lead to interesting pieces of filmmaking. From Duchamp to WW2 propaganda by Frank Capra.

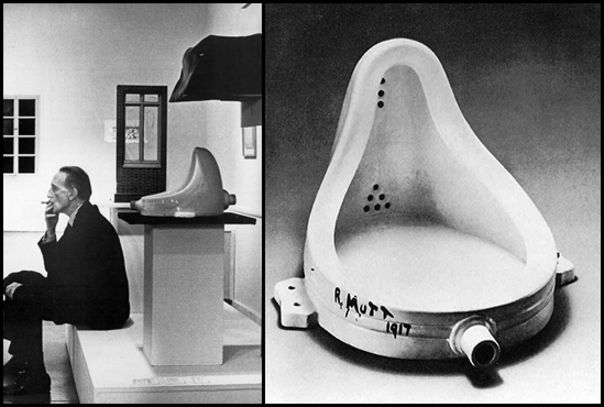

Duchamp's provocation

The legend goes like this: Duchamp got a urinal and displayed it as a work of art in a museum exhibition. As usual, things are not that simple. In fact, the urinal (signed by Duchamp with the pseudonym Richard Mutt) was rejected in 1917 by the Society of Independent Artists and was displayed 33 years later, in 1950, in New York City. Between 1917 and 1950, there were many comings and goings, endless debates and quite a few urinals. But, in a sense, the details are not important, so let’s just say that Duchamp got a urinal and displayed it as a work of art in a museum exhibition. This act generated a considerable scandal because it destroyed (or at least brought to question) many suppositions regarding art and artists: how could it be that a work of art was produced by a urinal factory and not by an artist? How could it be that technique and hard work were replaced by a whim? How could it be that the work displayed was something serialized and not unique, an object exactly the same as thousands of others?

When the urinal was rejected by the Society of Independent Artists in 1917, the art magazine "The Blind Man" published the following: "Whether Mr. Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He chose it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object." To take something that has a specific purpose, to change its context so that it loses its original meaning and to relocate it to give it a new sense: that is exactly what found footage does; except for the fact that it uses images instead of urinals. The director of found footage films precisely takes images shot by other people and uses them to create something personal and new.

One of the first examples is John Cornell and his short film ROSE HOBART (1936). Cornell, an artist from New York, frequented antique shops, warehouses and garbage dumps. One day, in one of his walks, he found a copy of the low budget adventure film East of Borneo and picked it up. When he watched it, he started feeling two things. One, that the film was soporific. Two, that he was falling in love with the actress Rose Hobart. So he got a pair of scissors and tried to improve the film, cutting the scenes which he felt were boring and leaving the ones in which his beloved appeared. When he finished, he had reduced the film from 77 to 18 minutes. As a final touch, he added images of an eclipse, which he took from another movie. ROSE HOBART became well-known in some circles and was projected, through a blue filter and with a Brazilian song as a soundtrack, in several museums. A dull feature film, with synchronized sound and a defined story line, became a semi-silent, hypnotic and mysterious short film. The images weren’t tied any more to a spatial-temporal logic but rather to an oneiric one. In fact, they say that during one the screenings a furious Dali started kicking the projector and shouting to Cornell, "You stole my dream!"

Six years later, in 1942, the US Army entrusted Frank Capra the production of WHY WE FIGHT. The story is better known and much less poetic than ROSE HOBART's - the United States were about to intervene in the Second World War and the Government needed to explain to the soldiers why it was indispensable to fight. So they called Capra, who had never directed a documentary film, entrusted him with the mission and provided him with plenty of images. They were of different sorts and different origins: full-length narrative films, educational movies, documentaries, short films, newsreels, etc., produced in the United States or in the allied or enemy countries. Capra and his collaborators spent months going over the images and finally took what they needed, reordered it, added some maps and a voice over (in fact, two voice overs) to produce WHY WE FIGHT. In this documentary series, the voice over is essential. The images often seem unconnected and the voice over is the only thing that keeps them together. A baseball match, a car cutting through a desert and two fishermen in a small boat find a connection through the line "we Americans love sports. We enjoy travelling. We hunt and fish." Capra and his team turned an overwhelming amount of footage into a series of almost seven hours, with the objective of motivating the American soldiers, extolling a set of ideals in opposition to others, reconstructing several battles and describing the idiosyncrasy and the history of the most important belligerent nations. All this using images produced by others, shot with completely different intentions.

ROSE HOBART and WHY WE FIGHT are two radically different films. One lasts 18 minutes, the other seven hours. One was produced by a single person, the other by a big team. One was a personal initiative and had no external financial support, the other was entrusted and funded by the US Government. One doesn't have a clear objective, the other does. One is elusive and sensorial, the other transparent and argumentative.

Nonetheless, they both have something in common - they take images produced by others and use them for their own purpose. Through editing, voice over, chromatic alterations and the use of music, the images are transformed into something else. A close-up of Rose Hobart stops being the element of an adventure plot and becomes a hallucinatory image. A scene of a baseball match stops being an anodyne moment of a newsreel and becomes a symbol of the American passion for sports.

ROSE HOBART and WHY WE FIGHT embody two different types of found footage films: the appropriation of images for experimental (the former) or documentary (the latter) purposes.

301 Moved Permanently