The fault in our shooting stars

by Miro Frakić

"Dead bodies!", she shouts. Visions of the future in the arts rarely ooze with optimism, but with an author as cynical as Don Hertzfeldt, one can be certain that the story will reach Beckettian proportions. Otherwise loved and notorious for his surreal tragic comedies about socially and existentially awkward people (Lilly and Jim, It's a Beautiful Day, Billy's Balloon), Hertzfeldt now returns with the 17-minute World of Tomorrow to deliver an additional blow to the notion of humanity. 227 years into the future, the shooting stars are bodies of people who cannot afford better teleportation services to flee the doomed Earth. What used to be the symbol of wishful possibility is now but a symptom of social injustice.

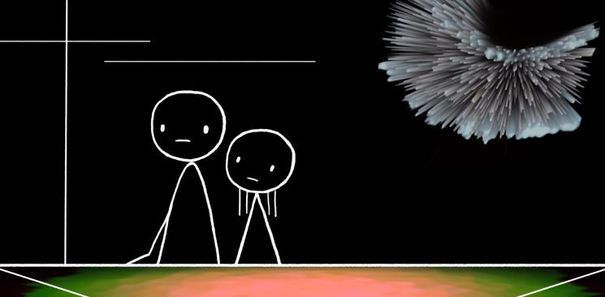

It was in the Sundance-curated shorts programme at the 21st Sarajevo Film Festival that the audience got to experience Hertzfeldt's latest work. The wicked animation starts rather simple – with little Emily approaching a phallic videophone to receive a call from her future self, the third-generation Emily clone. A grim account is delivered of what the future holds: dehumanized, desensitized and alienated human beings binge-watching the memories of their previous incarnations in search for a sense of self. Estranged from themselves, they are stuck in an inexplicable feeling of nostalgia, unable to fully grasp the world around them. Thus, while the background changes, shifts in shapes and colours, the people of tomorrow barely move—everyone save for little and blissfully ignorant Emily. There is still naïvety left in her to feel joy.

At its core, World of Tomorrow is a typically forceful, in-your-face Hertzfeldt affair, transposed into the future. He is very unsubtle about what he wants to say – future Emily is fairly blunt in making a point that there is no real connection possible anymore. With no “mental and emotional capacity” to process her feelings, her love affairs include a rock, a gas pump and a brainless clone. Memories are, then, the only human quality they have left. These, now digitalized, are being passed along the line of clones for pseudo-life purposes.

Interestingly enough, the World of Tomorrow also marks Hertzfeldt's leap into digital animation. His characteristic black-and-white, simple-shaped style of human subjects is complemented with the digitally manipulated colours, shapes and lines of their surroundings. Although unusual for the director, the mix works well as an organic whole.

However twisted and amusing, World of Tomorrow feels somewhat weaker compared to the author's previous works, such as the daringly novel Rejected or the darkly comical Everything Will Be OK. The two Emily's are endearing but ultimately monotonous in their interaction, which dilutes the film's original vision. At that point, its nonchalant ingenuity is at risk of being lost on the viewers, which would be a shame as Hertzfeldt is truly one of a kind in the animation world.