Prehistoric Interiors of the Chauvet Cave

Werner Herzog's CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS not only tells us about the prehistoric past but also about our complex and paradoxical point of view when dealing with our history, says Rubén Padrón Astorga of the Talent Press Guadalajara.

THE CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS

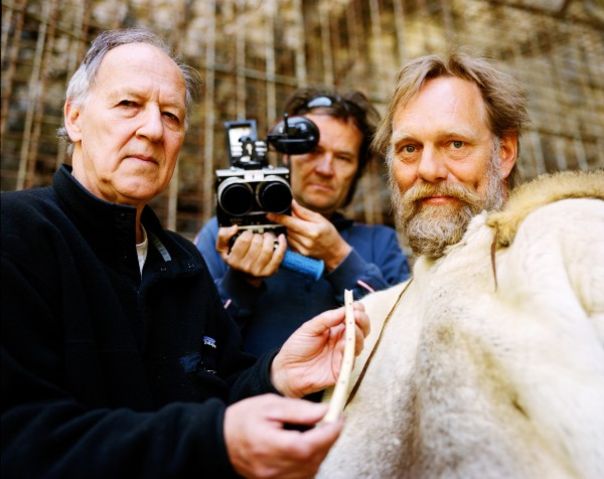

Werner Herzog was the first to film the French cave of Chauvet, which in its interior conserves the intact remains of a past that until recently has been closed and protected from the passage of time. Asleep for centuries, far away from progress and evolution, the remains of prehistoric life were frozen when a landslide blocked the entrance, and the salty tears of the cave preserved the original drawings in a blanket of calcium.

In THE CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS, Werner Herzog describes the hidden secrets of the cave where the oldest cave paintings known to man are to be found; images that report the events of daily life, like battles of wild beasts or the gallop of horses, or the contours of the naked body of a woman. Thanks to the contrasts and ingenious graphic solutions that suggest movement, the figures revive and appear to feel the impetus that inspired successions of artists to paint them: their fury is revealed in their eyes, the emotion in their muscles, and they return in these images to their eternal struggle for life.

One of the things that make this movie really extraordinary is Herzog’s ability to momentarily disconnect from what he describes. The true beauty and essence of the paintings is not revealed until one looks away for a moment. Cadavers of animals, bones swept in by water, trampled gigantic fossils, calcified sculptures of unknown origin adorn the floor of the cave and document the experiences of human and animal life that they have witnessed. The paintings are not isolated creations, as they usually are in most caves known to date, where time has continued to pass and the past has only been preserved in the paintings. Here the images are expressions of the life that created them in what is for us an incomprehensible reality, but which has left traces that like suggestions leave room for speculation.

For Herzog the scientific evidence is less important than speculation. When the historic data is obscured, his questions are asked through his aesthetic impression; he follows the path prescribed by written theory, but enlightened by emotion. He asks a scientist to explain archeological arguments, but then allows an expert in perfumes to interpret the smells of the cave. He accepts that he is not allowed to approach a painting in the interest of preserving the cave floor, and only observes the side of the drawings. Then, however, without explaining how, he shows the hidden side, the piece inaccessible to science.

The cave was never inhabited, only a place for people of the plains to visit, where tools, sculptures and weapons have been found. Outside of the cave there is no remaining trace of human life, but the description of the caves would have been incomplete if the film crew had not at least walked along the paths that were once walked by those that frequented the caves, or if they had not tried their weapons and interrogated their sculptures.

Herzog goes beyond himself. On the one hand, he interprets signs of an ancient life expressed in a cryptic language. On the other, he questions his own capacity to interpret. The present is not a finality, but rather only one layer of history and not necessarily even a progression within it. For example, as is mentioned in the documentary, reality was more porous for prehistoric man than it is for us: a man could fly and a tree speak. For Herzog, interpreting the remains of an ancient life from a modern point of view is a profound paradox. His candid perspective reminds us that our will and our tools for comprehension may be totally inefficient when approaching prehistoric life. This not only lends credibility to the documentary, but also conditions our attitude towards it, and it gives our view a tension and drama not often associated with the genre, and this stimulates the establishment of relationships between passersby and the complexities of reality.

The documentary was filmed in 3D, a technique that allows us to touch the cave, push into the background unnecessary information, and focus our eyes on the significant and attractive information. The three dimensional image is less arbitrary in cases like this one, when it does not attempt to attack or surprise, but instead illustrate and help explain.