Exiliar de la memoria (Exiled from memory)

by Jaqueline Avila

"For the men who will never be children. For the children who search for their father. For the parents who no longer know their children. For my future children I can finally dream about." - Bernard Bellefroid (final dedication of the Regatta)

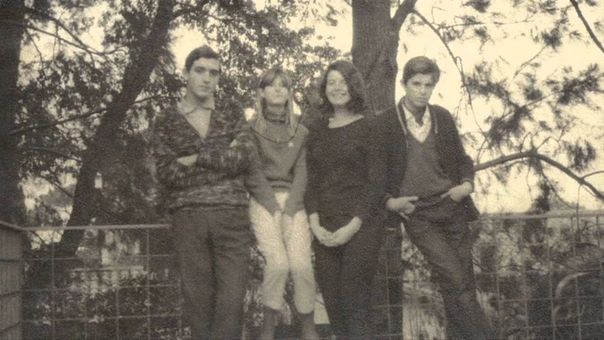

Tiempo suspendido (Suspended Time), the documentary by the director of Argentine origin who settled in Mexico, Natalia Bruschtein, reflects faithfulness to memory, the reconstruction of what has been experienced, and how telling about something ends in adulterating it, in blurring its pain, in forgetting it. It is based on the story of Laura Bonaparte, her grandmother, who evokes a dual struggle with her life: to oppose the forgetfulness of historical justice, to be an active element in the struggle of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo (Mothers of Plaza de Mayo) and of her own children, who disappeared in military-led Argentina of the 70's and whose only anchor with the present is, precisely, the fact of being remembered by their mother. Bruchstein is at once narrator and incidental protagonist of the pieces of memory that her documentary brings to the present with a story that feels more empathic and lively than maudlin or overwhelmingly dramatic. Natalia's debut is a heartfelt tribute to her grandmother, diagnosed with senile dementia, and at the same time manages to chronicle the times with newspaper readings, thoughts, her protagonist's poetically-made testimonies—perhaps based on the facility Argentines have for writing—and of archive material like family photographs or excerpts from a documentary about the cause of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, that Argentine "History" that is woven from individual dramas. Bonaparte's tragedy: three of her four children "disappeared" between 1975 and 1983, three State Crimes to which she dedicated her mind, efforts, struggles and memory, in which they came together over the decades and which, perhaps by their own accord, are allowed to leave drop by drop as dementia takes control of her mind and clouds everything, making it all disappear. Bruchstein's approach to her grandmother's story, into which she successfully fits her own reflective concerns about memory, brings to mind, on the one hand, the honest and compassionate tone of Alan Berliner's First Cousin Once Removed, the documentary x-ray about the deterioration of the poet Edward Honig and his memory due to Alzheimer's disease, and also the emotionality of a personal narrative, emerging from the filmmaker's more direct environment: her own family, like that of David Sieveking's Vergiss mein nicht, fashioned by the German producer from the exposure of her own mother’s loss of memory. Bruchstein's directorial debut takes it a step further, however, and projects the ambition of the director herself, who precisely and almost metalinguistically underpins meditations on memory with the extraction of her grandmother's "I can't remember" (simulated, perhaps fictitious, which may even be contradictory to the documentary format of the film); questions, pictures that are put before the eyes of the octogenarian, confronting the perhaps self-imposed oblivion that was once cause for combat, monstrous worship of the facts in their repetition to demand justice, today a historical, cinematographic account. The relentless candor of Tiempo suspendido (Time suspended) demands a rethinking of memory, that which many times cannot be explained, that cannot be grasped, which does not have a way of being and that leaves a feeling that, at times, existence is anchored in unfinished memories.