Reorientation: Secrets and Alternative Archives

By Jesse Cumming

© UFO Production

Any archive, whatever its ostensible or official aim, can double as some sort of open secret. Historical but hidden, the material of any archive is activated though contemporary engagement. A number of works in this year’s Berlinale Forum and Forum Expanded also reveal the productive shifts that take place when non-narrative or industrial film material is placed in the context of a feature-length film, presented and watched as art. In utilising alternative archives, works like Ruth Beckermann’s THE WALDHEIM WALTZ and Julien Faraut’s IN THE REALM OF PERFECTION gesture toward the concealment and revelation of unseen secrets.

Elsewhere in the programme, Kristina Konrad’s UNA PREGUNTAS, produced in collaboration with editor René Frölke, who earns a “dramaturgy” credit, utilises the narrative structure of an election and her personal archive of Umatic tapes to trace a major Uruguayan referendum in 1986, shortly after the end of military rule. In his short piece EVIDENCE OF THE EVIDENCE, Alexander Johnson adopts original police footage from the 1971 Attica prison uprising to retrace the events, gesturing to the narrative and pseudo-thriller elements of the stand-off, as well as the narrative that later emerged about the role of police violence.

In collaboration with SAVVY Contemporary, Jasmina Metwaly’s WE ARE NOT WORRIED IN THE LEAST utilises activist footage from the 2011 uprisings across the Arab World. While not specifically structured as a feature film - instead presented as a multichannel installation – the work engages with similar questions about context and reception through the use of relational aesthetics, placing the raw footage within the realm of fine art.

Worthy of particular consideration is IN THE REALM OF PERFECTION, the debut feature by French filmmaker Julien Faraut, in which the director playfully interrogates the connections between cinema and tennis, and more generally, sports. Taking Jean-Luc Godard’s axiom that “cinéma lies, sports don’t”, the film riffs on such a claim with a piece that expands to reflect on questions of perception and professionalism, as well as the irreconcilable gaps (or irretrievable secrets) that exist between them.

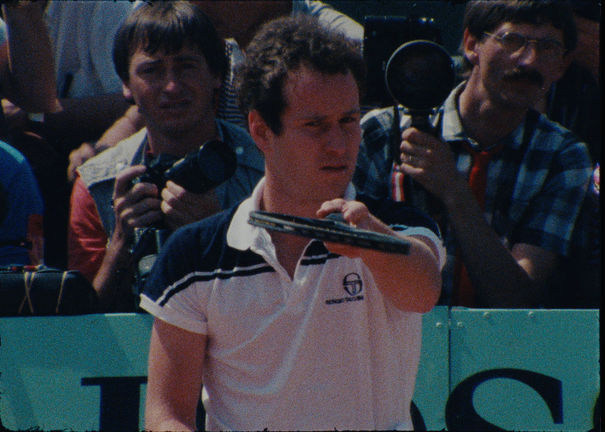

The film is constructed almost entirely using 16mm footage of John McEnroe, shot in the 1980s by Gil de Kermadec, France’s first technical director of tennis. Slowed down and otherwise manipulated, with added asides of computer animation and instructional films, the work is also accompanied by Faraut’s voice-over text (here narrated by Mathieu Amalric).

Ruth Beckermann’s THE WALDHEIM WALTZ is also assembled using 1980s archival footage – in this case primarily Austrian and international broadcast news coverage of the Waldheim affair, which saw the public interrogation and controversy surrounding ex-Wehrmacht soldier Kurt Waldheim during his run for the presidency. The filmmaker also introduces an element of personal archival excavation, as she incorporates her own jittery video footage taken during contemporaneous public protests against the former Nazi.

In each of the works, secrets and fragments operate first on the level of content. In Beckermann’s essay film the principle, obvious secret concerns Waldheim's wartime past, written out of his own autobiographies steadfastly denied with the slippery rhetorical skill of a politician. Of course, in ways Waldheim stands as a social synecdoche for the shameful secret of Austria’s capitulation and collaboration with the Third Reich – an open secret that many seem resistant to acknowledge.

The secret of skill and its limitations is playfully interrogated in Faraut’s film, as it endeavours to understand both the unique talents which made McEnroe one of the world’s greatest athletes, and what caused him to squander the US Open to competitor Ivan Lendl in 1987, a match that occupies the film’s entire final third.

Prior to the showdown, the film introduces several sequences that attempt to uncover and explain McEnroe’s unique skills. The first approach is physical, with a playful analysis of the athlete’s form – complete with on-screen animations and diagrams. The connections between sport and cinema are further extrapolated by way of an aside considering the proto-cinematic photography practices of Etienne Jules-Marey and Eadweard Muybridge, as their chronophotography captured human and animal bodies in motion for the sake of analysis.

From the realm of the physical – McEnroe as a model of form – the film advances to offer a complementary consideration of the psychological. Through montage and narration, the film examines McEnroe’s temper and demands for precision asking to what extent, if any, the notorious explosions play into the secrets of his craft.

Moving from the the level of construction and the diegetic secrets of the two works, we might also look at the secrets that exists in their use of specific archives, particularly the reliance on non-cinematic archives. In this context we see the ways each film plays with questions concerning the original intention in the footage at hand. Here one is reminded of Farocki’s investigations into industrial images that serve no cinematic purpose, and are often pronounced with no consideration for the human spectator.

Of course, archives are themselves political entities, equally notable for what they contain as much as what they exclude. It’s here that the preponderance of international news footage in THE WALDHEIM WALTZ – making up for a death of original Austrian reporting about the original anti-Waldheim protests – points to a productive gap in popular knowledge. Beckermann here endeavours to plug such a gap, at least partially, through the inclusion of her own on-the-ground footage.

Unlike Beckermann, with IN THE REALM OF PERFECTION Faraut sources his material predominantly from a single archive: the ‘Institut National du Sport et de l'Education Physique’ in France. Throughout the film, the piece actively interrogates the relationship between cinema and sports related to dramaturgy and the question of time – most notably with a citation from French critic (and tennis enthusiast) Serge Daney about the similarities between the sport and directing (here is it worth considering institutional questions and the purposes of the given films. The question of sport cinema and archiving is an under-explored topic – especially when one is reminded that the largest collection of 16mm films in the United States isn’t housed in any Hollywood studio or the Library of Congress, but in the the National Football League archives, a point of inquiry beyond this immediate scope).

Both Beckermann and Faraut are keenly aware of the question of dramaturgy and narrative in the construction of non-fictional cinema, and each of the films and filmmakers embrace certain real-life narrative forms for the sake of cinematic storytelling. For Faraut, an individual tennis match provides a narrative grounding for the final movement of the film, at which point the physique and psychology of the central character is placed into a science-like experiment for observation. For Beckermann (and her editor Dieter Pichler), the structure comes in the form of a national election, with its natural arc and eventual climax. Despite the fact that any viewer might know what happens at the end of the narrative, in each case the unconventional material is reworked into an unexpected context with new affective potential, whether to agitate or to stimulate.

Despite assumptions of the truth claim of documentary and the camera’s capacity to reveal – something introduced through PERFECTION’s references to chronophotography – each of these films retains secrets and unknowns. With PERFECTION the question of perspective emerges as a theme throughout and exists as a repeated point of conflict, as over and over we watch McEnroe argue with the officials about their calls and question their ability to judge objectively, while the reasons for McEnroe’s proficiency and its eventual shortcomings are oblique and unanswerable. With THE WALDHEIM WALTZ, despite the wealth of material, in the end the titular figure never emerges into a relief as clear as one desires and remains a shifting, impenetrable enigma – seen but unknown.