Water as metaphor in El botón de nácar by Patricio Guzmán (2015)

By Libertad Gills

“Chile is a country to roll up”, said Patricio Guzmán in the Argentinean premiere of his latest documentary El botón de nácar (awarded Best Screenplay at Berlinale). To illustrate this idea, an artist brought by Guzmán draws a long, thin map of Chile, which needs to be unrolled carefully by a group of young helpers. (The fact that they are young is not only a detail: it is intentional, for, according, to Guzmán any hope of change takes place in schools and through education).

If Chile is a country to roll up, Guzmán is one of its most important cartographers. For decades, he has been observing closely the most problematic particularities of his country and showing them to his compatriots. In his latest work, Guzmán argues that Chile “is a country that lives giving its back to its most important element”: the sea. He wonders why the sea in Chile has been denied in such manner. What meaning does the sea have? What secrets does it hide? Guzmán answers these abstract questions with the metaphoric language that only film, through its combination of image and sound, can make use of.

Technically speaking, the film is impeccable. The image is worthy of an IMAX cinema (I would love to see it in this format). The sound design deserves to be studied separately. It is mainly through working meticulously with the sound that Guzmán reflects on the core subject of the investigation and conveys his perspective from the beginning to the end of the film.

The film begins with a close up of a quartz cube over a black background. I immediately thought of an ice cube (afterwards, the film ends with this) not only because of its texture, but also because of the water sounds that accompany it. Guzmán’s voice off screen explains that the quartz is 3000 years old and contains a drop of water. From the beginning, Guzmán invites us to listen to the sound of water, an element we usually ignore, which, nevertheless, is undoubtedly the most important one of life. With the image of the quartz and the sound of water, Guzmán creates a contrast resulting in an effect of mystery and amazement. We feel we are inside the quartz, observing the immensity of the universe from an incredibly small space.

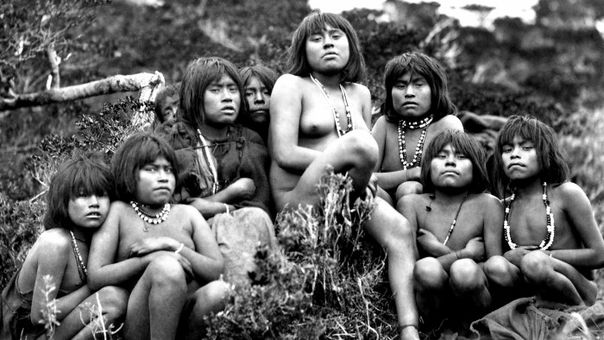

Indigenous peoples believe, says an anthropologist named Claudio, that all stones, plants and animals have their own voice or song. Claudio, a character who would fit perfectly in a Werner Herzog documentary, imitates the sounds of water, which Guzmán sets against some images of a river. We then meet a woman of the Kawésqar ethnic group, one of the indigenous peoples of the south of Chile and Argentina, who were practically exterminated by colonizers and by cultural “assimilation”. Guzmán, who appears to be very close to her, asks her to tell the story of her trip through the ocean in her native language. At first, her words come out like water from a tap hitting against a surface: they sound like random, hard words, without any context because we are not able to understand them. We continue listening and the words acquire new forms. When we start to understand the sound and rhythm of the Kawésqar language – an exercise that only happens because Guzmán is making us really listen to the language – words start to flow like water running through a river with a bed of stones. The sound of the Kawésqar language is not so different from Claudio’s song. Through the association produced by the images and sound, we understand that if water had its own voice, Kawésqar would be its language. If water could communicate something, then it would be the story of the genocide of the indigenous peoples.

Guzmán doesn’t stop there. His story travels from past to present, connecting with brutal force the genocide of our indigenous peoples with the disappeared persons from the military dictatorships of the 70s – some of whom were drugged and thrown into the sea. The disappeared “were victims of a violence already known by the indigenous peoples”, says one of the speakers. Guzmán forces us to think about something very abstract, but also very serious: if we had taken the time to listen to the sound of water, would we have been able to hear the pain of the indigenous peoples and maybe prevent the story from repeating itself?

The documentary’s rhythm and musical structure are determined mainly by the editing and sound design. After the intervention in Kawésqar language, the film takes off and enters a sharp crescendo until the end. The presence of the director and his confidence as an artist and communicator of ideas has an overwhelming force. There are only a few directors with this characteristic. Another director would be Chris Marker, with his masterpiece “Statues also die” (1953). This ethnographic essay analyzes how colonial thinking has put African art in a space which denies its essential power (They say that after seeing Guzmán’s first picture, Marker gave Guzmán film to shoot his next film La batalla de Chile. Marker’s support was very useful for Guzmán’s career)

After the screening at Village Recoleta, as Guzmán’s presence had not been announced, many spectators left the cinema. They came back hurriedly when Guzmán, with a microphone in his hand, suggested: “We could talk for a while”. The audience answered with a huge applause. There is no doubt that El botón de nácar will make us think and talk for a while.

Mariángela Martínez Restrepo Talent Press BsAs Coordinator Clara Picasso Text Translator