On the target of a 4K

By Bruno Galindo

Intervenção

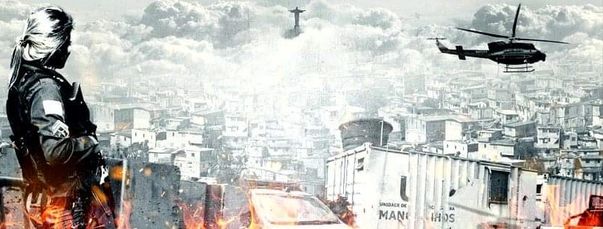

During the screenings of the 21st Rio Int’ Film Festival, and in the process of finding a theme for an essay that would answer the concerns that arose during the event, four Brazilian films seen during the Talent Press program drew my attention to a loud filmic standard: the use of panoramic shots to depict spaces of Rio's slums. In this essay, one that concludes a journey of doubt, conflict, and good exchanges, my text will point to these choices in the documentaries Minha fortaleza: Os filhos de fulano (2019), by Tatiana Lohmann, and Fé e fúria (2019), in the fiction feature Intervenção (2019, pictured), and in the experimental short Copacabana Madureira (2019).

The use of the panoramic shots gains centrality in this text in the same measure as the recurrence of this choice was noticeable in the festival program. The question that we will try to answer here then is: what is the relationship and which are the effects of the use of this framing in the process of filming the material these works intend to show? Such a question will lead to the final thought: Is there an essentially violent way to film the “quebradas” (the favelas)?

The first question begins to be answered by the observation of Marcos Pimentel's documentary Fé e fúria. Taking as a subject the increase of violence in neo-Pentecostal discourses against Afro-Brazilian religions, the film builds a dense discussion on the subject. However, by resourcing to panoramic shots to film the slums, the documentary creates a dangerous relationship. For example: when one of the people interviewed talks about the presence of drug trafficking, right after the film shows two young blacks prancing kite on the roof. Intentionally or not, the choice of this shot, associated here with such discourse, risks a blatant and constant determinism in the use of this frame – what is shown can be activated as a potential supporting material for the content of the interview. This thin line is also noticeable in Tatiana Lohmann's Minha fortaleza.

Resourcing to wide shots even in a more problematic way, regarding the film’s proposal, Lohmann (who is also the editor) opts for a recurring use of panoramic views that, either in its capture or in the way they are articulated, tend to print the discourse of the film in a space of generic collectivity (children, people and alleys are filmed in the “plural”), which can also make the material of the lives and bodies that are being filmed generic. This procedure turns the space almost into a blank page for future printing of any speech imputed or intended by the film. As critic Lorenna Rocha pointed out in her conversation with the director during the Talent Press program, there is an ethical problem present in the construction of a discourse in which parental abandonment is illustrated with panoramic shots of anonymous children from Vila Flávia running in the alleys, as if they were abandoned into the world. This choice may do the film a service, but it does a “disservice” to those who are being filmed. This “disservice” becomes even more violent in the feature Intervenção (2019), directed by Caio Cobra.

Betting on general shots filmed from above, Cobra’s film expresses its violence both in the drone flyover, which starts from the same ethical place as the police war helicopters or from the sensationalism of TV shows, as well as in the impression, in those images, of a political speech of surveillance over an alleged violent or dangerous space. This same space, as seen from the ground and from within, can express precisely the antithesis of this discourse. When shooting houses and shacks emptied from the distance, the framing becomes a restraint, and the camera no longer deals with the police to become the police.

This very same film – by the way, source of the curtailment episode I experienced as a result of an arbitrary decision of the festival (tinyurl.com/uhh2pfc) – then evokes an answer to the second question mentioned in this essay: are there more violent ways of filming the “quebradas”, and one of them includes the relationship between wide shots and tools that evade, such like drones, an implication with the space that is being shot. I believe that today it is impossible to ignore the ethical consequences of filming slums with aerial shots and at a distance. It is therefore necessary to consider why a festival such as this accepts and selects these images and, moreover, legitimizes them, while delegitimizes and supports attacks on critics that attack these old-fashioned and police-looking glances. Even because, instead of such common places as those mentioned above, we have examples of films like “Copacabana Madureira”, by Leonardo Martinelli, which makes use of this very same tool in a very distinct key.

In its beginning, this short movie from Rio de Janeiro opens with a panoramic shot that films the space of the favela. The first filmic gesture that goes beyond the police-like imaginary is the use of a soundtrack that, leaving aside clichés directed to initiated ears, moves into a piano track, which actually changes the spectator's relationship with the space. As these general shots consolidate themselves as ways of locating the space, then, the editing gradually places us (truly) in that place, in a dignified and respectful manner. And although it is a fragile film in many ways, this sequence, among the films seen at the festival, is the one that most helps to unveil that the problem of what to film is always a problem of how one chooses to film – a problem of who is objectifying, not of the filmic object – and that there are other ways of thinking the general and panoramic shots as locating internal, near and living spatiality, rather than being at the service of maintaining a distance.

At the end of this route, the two initial questions find important answers in this text, pointing out that in the camera that places itself within a distance of what’s being filmed there is the imminence of a mistaken or violent projection over the favela spaces. Even today, in the country in which we live, aerial and general shots of slums and hills seem only to reproduce, in a cinematographic code, racially violent and socially deterministic surveillance images. Whether in the movies or in news coverage such as those that reported the invasion of the Complexo do Alemão in 2010, the choice of using general and panoramic shots is very political while selling itself as apolitical. And in this game of general and generic film politics, one final question will be placed: what is more accepted: these imagens or the criticism directed to them? My experience here at the 21st Rio Festival points to the first possibility, a fact that is worrying but, at the same time, shows much of what Brazil is – not just from above, but from within. .