In Search of El Dorado

Ruben Demasure of the 2016 Talent Press analyses the motif of the mythical El Dorado in several Berlinale Forum films.

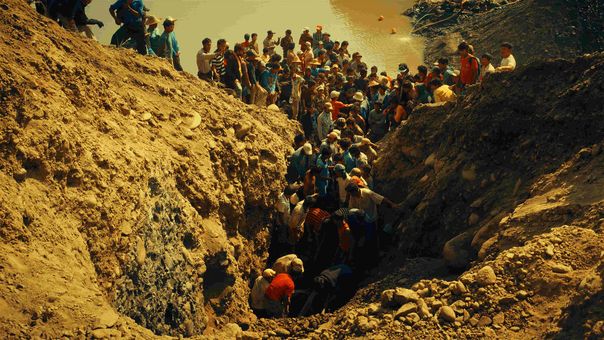

Midi Z's documentary CITY OF JADE.

“Shadow,“ said he, “Where can it be – This land of Eldorado?“ (Edgar Allan Poe, “Eldorado”, 1849)

While critics mine film festivals for hidden or sometimes unattainable gems, a parallel quest for an El Dorado can be seen as a thematic undercurrent within the Berlinale Forum’s larger focus on migration, especially apparent in the following films. In ELDORADO XXI and CITY OF JADE, Salomé Lamas and Midi Z look at gold and jade mines in the Peruvian Andes and northern Myanmar respectively. Set in the same war-torn region as the latter film, Wang Bing’s TA’ANG follows people from the eponymous minority group seeking safer shelter across the Chinese border. In AN OUTPOST OF PROGRESS and LETTERS FROM WAR, the Portuguese Hugo Vieira da Silva and Ivo M. Ferreira deal explicitly with the colonial connotations of the notion of El Dorado. Their compatriots Sergio da Costa and Maya Kosa follow an eternal wanderer searching for a personal state of grace in the semi-documentary RIO CORGO.

Historically, the tale of this mythical city of gold has inspired a number of futile expeditions among sixteenth century conquistadors. Since then, the concept of El Dorado underwent several transformations: from a legendary location where wealth could be rapidly acquired, to something one might spend one’s life seeking but may not even exist. The longing for a fabled city of gold not only shined through as a socio-political motif but also translates in terms of how the filmmakers utilize sound, texture and lighting to evoke this realm of myth and imagination.

In Light of

Published the year he died, “Eldorado” is one of his last poems Edgar Allan Poe penned. He uses the term shadow in the middle of each of the poem’s four stanzas. The meaning of the word, however, changes with each use. What first stands for a literal blocking of the sun comes to connote gloom or despair and finally evokes a ghostly presence. There are rhymes between all six films that reveal variations on these metaphors to frame the quest for El Dorado.

ELDORADO XXI’s signature long shot recalls the astonishing opening image of a trail of men trudging up a Peruvian mountain side in search of El Dorado in Werner Herzog’s AGUIRRE: THE WRATH OF GOD (1972). Only in the prior, Salomé Lamas holds the static camera shot for one hour. Similar to Herzog's, people disappear behind a hillside turn in the background to reemerge in the middle of the frame and ultimately, in the immediate foreground. It’s depicting the change of shifts of the workers of a gold mine situated at the highest elevation in the world. Dusk turns into pitch black night and the Sisyphean snake-like shape turns into a vertiginous dance of helmet headlights.

In CITY OF JADE, Midi Z reunites with his brother who left his family sixteen years ago to become rich overnight in the jade mines. More noteworthy than the personal or political backstory is its saturated color palette and texture of the digital noise. Right at the beginning of the shoot, the director’s camera equipment was confiscated by the Burmese army. Therefore, all the footage was shot in secret with consumer cameras. The images’ digital noise cinematically erodes the luster of the diggers’ dreams and desires. The image is imbued with a matte-like gold light. Orange hues haunt the hills and contrast with the stark blue tarps on top of the miners’ shacks. The poisonous palette cast the environment in an expressionist, surreal and psychedelic impression of his brother’s opium-infused, mental landscape. This attempt recalls Marcel L’Herbier’s EL DORADO (1921). This painterly picture, in which a mother tries to find her fortune in an Andalusian cabaret called “El Dorado”, was among the first films to evoke a subjective expression of a character’s world trough psychological color tinting, and distorted, out-of-focus shots.

The latest films of Wang Bing and Midi Z take place in the same geographical region and also share a similar camcorder aesthetic. However, Bing’s images have a straight, unprocessed look. The central section of TA’ANG takes place around a campfire where the eponymous Burmese refugees tell stories about home. Bing uses the burning flame as his single light source, resulting in a DV-aesthetic with burned-out blacks. An unsteadily shining candle in the middle foreground creates a flicker that renders a deaf-mute woman in ghostly shadows.

Bing and Midi Z’s visual style couldn’t be more different than the overstated lush of LETTERS FROM WAR. Here, the noirish low-key lighting casts stark shadows over the contemporaneous conquistadors’ cause. In the two other Portuguese features ghosts appear in the flesh. In AN OUTPOST OF PROGRESS Christian saints and notorious historical colonials, come out of the foggy forest to visit the ivory-hungry functionaries. In RIO CORGO the wandering protagonist Joaquim is visited by his own image and ghosts from the past. In a dream, a girl swaps his richly embroidered sombrero for a golden crown. Standing in a spotlight against a black background, he laughs out loud. Moments before the dream we see him gazing at a piece of fool’s gold. He has reached his own spiritual freedom echoing that of the original myth, in which El Dorado is not a place but the legendary golden king, El Rey Dorado, when Joaquim expresses: “I do what I want. I go where I want to go.”

Silence Is Gold

In Poe’s poem the antihero, “journeyed long, singing a song.” The sound and pronunciation of the poem are as important as the words. The form and meter of the verses, the play with syllables and the beats at the end of the lines help to express the disappointment and fruitlessness of the journey to El Dorado. In the majority of the films, offscreen sound evokes either the unattainable El Dorado or the place people have abandoned, leaving them in a sort of no man’s land.

In TA’ANG, the war is never shown but is present by the aural impact of bombs in the mountains. The kids imitate the machine gun’s tatata-noises. Similar to his previous film, FATHER AND SONS (2015), the frequent inclusion of shots of mobile phone use, reveals that their forms of communication are simultaneously modern and ancient in their fireside storytelling. In contrast to Bing’s observational approach, Midi Z asks his brother questions directly from behind the camera and provides the voice-over himself.

Virtually a film without dialogue, In LETTERS FROM WAR the letters of a doctor serving Portugal’s crumbling empire in Angola are read in voice-over by his wife. His descriptions of her (“Ingres profile”, “Botticelli portrait”) would have stressed his longing better without the few shots of her. She’s his gold, calling her “my country, my land,” while at the same time confessing he would be a foreigner or intruder anywhere else.

In ELDORADO XXI, Salomé Lamas relies on offscreen sound design for her one-hour long take. She constructed a multi-layered sound piece to the static frame, consisting of testimonies and excerpts of the mine’s own radio station. The added sounds range from the workers’ footsteps to over-the-top and cheesy cave-like drippings, church bells and seagulls. “There’re almost on the edge of a Harry Potter film,” Lamas says. In the second part, a Major Lazer reggaeton remix is placed over a frantic Spanish colonial dance in which masked miners loose themselves around a violently flickering fire. She goes against the standard ethno-antropological approach of only using direct sound recordings.

In AN OUTPOST OF PROGRESS there’s no access to the natives’ reactions because of a conscious omission of their subtitles. As the film winds down, it evolves into a silent film, including intertitles, piano accompaniment and a final iris frame. Accompanied on his journeys by accordeon music and Portuguese 70s songs, RIO CORGO’s picaresque explorer hits the road again in the closing frame…

“...Over the Mountains Of the Moon, Down the Valley of the Shadow, Ride, boldly ride,“ The shade replied – “If you seek for Eldorado!“