False Altruism

By Armando Quesada Webb

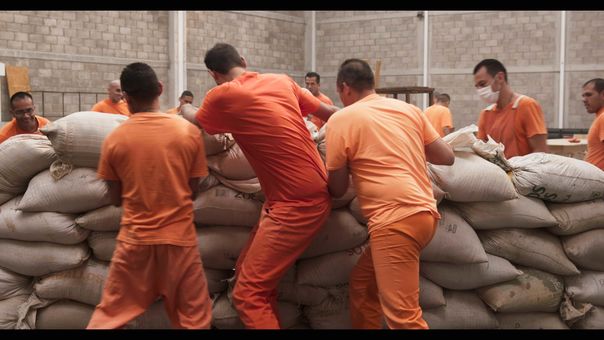

We when talk about others from a position of privilege, it is not at all uncommon to fall into frivolities and a sense of complacence regarding the subjects of our discourse. This is exactly what happens in 45 DÍAS EN JARBAR (45 Days in Harbar), a documentary film by director and visual artist César Aréchiga. The film is shot in the Puente Grande penitentiary in the Mexican state of Jalisco, where Aréchiga set up an art studio to teach painting and sculpture to fifteen inmates, establishing a dialogue with them in the process in an attempt to learn more about their pasts and so to humanize this marginalized population of convicted felons.

The film stimulates some interesting discussions, which would have been more valuable if they had been treated more fully: the question of whether prison is an institution that produces criminals, rather than reforming them; the lack of remorse on the part of many inmates; and their indifference to their own pasts. From the very first scene, however, 45 DÍAS EN JARBAR makes clear its objective: to move the viewer emotionally, at all costs. It is a work desperate to prove that it is born out of a sense of altruism, but it ends up caricaturing its subjects and rendering serious issues, such as drug trafficking and murder, banal.

So thoroughgoing is Aréchiga’s condescension, that even the prison environment, in which his main subjects find themselves, is presented as pleasant and welcoming: a place where one can sit down and learn to paint, while laughing about crimes committed on the outside. This is no exaggeration. There is moment in the film when the director is interviewing one of the prisoners, and he seems to be seeking a complicit smile from the viewer in response to a terribly painful story. Aréchiga’s claim to a humanistic purpose collapses completely at moments like this.

45 DÍAS EN JARBAR victimizes the inmates. When the director leaves off attempting to raise a chuckle, he seeks to make the viewer cry and feel sorry for the subjects of his documentary. There is no balance in his telling of their stories. The result is a manipulation, designed to make a gratuitous emotional impact, with no real interest in properly exploring the issues raised. On a formal level, the film is utterly conventional. The approach reminds one of television storytelling, with no interesting camerawork. Moreover, the use of music to reinforce the sentimentalism renders sequences already lacking in effect even more wooden. When the film seems to have ended, Aréchiga surprises us with a final scene, in which he himself appears, pondering and beginning a new creative process. A moment as unnecessary as it is artificial, which clears any doubts as to who the true protagonist of the film is. The documentary never really deals with the prisoners themselves, but rather with the savior who goes in to redeem them by means of his virtuous artistic labor. It is all no more than an exercise in egocentricity and self-healing. Complacent from beginning to end.

Translation: Gregory Dechant