Does the Berlinale Have a Nollywood Problem?

By Wilfred Okiche

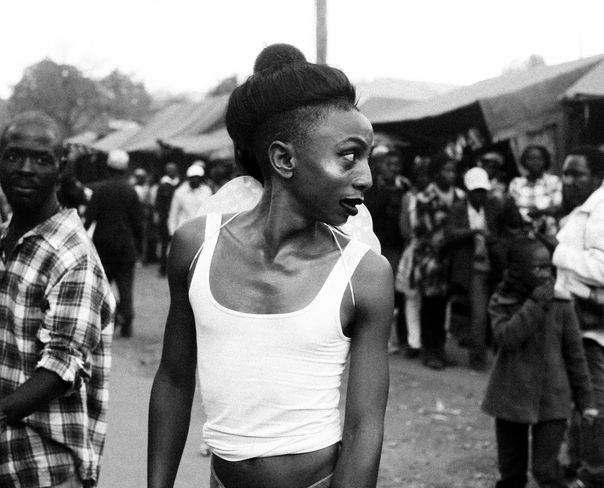

© Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese

The bustling Nigerian film industry – popularly known as Nollywood – is one of the largest film industries in the world, at least in terms of volume of output. The Berlin International Film Festival – popularly known as the Berlinale – is one of the largest film festivals in the world, and the only one among the three AAA festivals (the others being Cannes and Venice) that is not exclusive for industry players and the press. It has a huge audience. However, Nollywood remains largely missing from the festival programme, year after year. How come? Is it possible that there is not a single Nollywood film that could play in one of the several sections of a festival with such a drive for quantity and diversity? Is it possible that no Nollywood film could interest at least a small fraction of the Berlinale public?

It is nothing new that Nollywood’s presence at the Berlinale or at any of the other major European film festivals would barely register on the radar. For reasons that include paucity of quality, absence of interest or a general lack of understanding of the peculiarities of African cinema culture by western based programmers, compounded by a certain problematic expectation of what an African film should be, Nollywood has gotten used to cheering on the sidelines while films from southern or francophone Africa swoop in to grab all the spotlight.

This year, the South African road movie FLATLAND, a tale of two women on the run from the police, opened the Panorama programme, following in the tradition of the controversial same sex drama INXEBA (THE WOUND) in 2017. French-Senegalese director Alain Gomis, whose film FÉLICITÉ won the Jury Grand Prix award two years ago, this year is a member of the Best First Feature Award jury. Elsewhere, Lesotho born director Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese presented his first feature length, MOTHER, I AM SUFFOCATING. THIS IS MY LAST FILM ABOUT YOU in the Forum section.

After numerous conversations with festival delegates and journalists, one can figure out that screening at the Berlinale is hardly a matter of luck or chance. This achievement is usually the terminal stage of a long, arduous process of pitching, script development, labs and workshops, plus constant engagement and networking with programmers and festival delegates. But Nollywood is an environment in which films are traditionally shot and edited at fevered pacing, with the finished product churned out in a matter of weeks – then sent straight to video. Nollywood was born and developed as a phenomenon of the video era, partly because Nigeria, for many years, had no film theatres. With the reintroduction of cinemas at the turn of the 21st century, filmmakers started paying greater attention to the technical aspects of filmmaking, but the industry remains at its core a commercially driven one, borrowing heavily from Hollywood and mainstream Bollywood fare.

Even when they are richer and more perceptive, the stories tend to follow formulaic arrangements projected to attract as wide an audience as possible. Romantic comedies and all-star ensembles are huge, so are crowd pleasers and genre films. Huge grosses are more useful than glowing critical reviews and, because of this, filmmakers rarely factor the festival circuit – local or international – into their release or distribution plans. Tapping the local market exhaustively is all well and good, but proper attention from the international community might just be the key to developing the industry more comprehensively. If Nollywood is ever to be taken seriously, at least as a hub for quality cinema, the international festival is inevitable, and the Berlinale is one of world cinema’s biggest platforms.

But is the Berlinale really open to films from other regions that do not represent cinema in the context of the old European tradition? Dorothee Wenner, whose role as the Berlinale delegate for India, South Asia and Sub Saharan Africa involves constantly engaging with content from across these regions, certainly thinks so. As a programmer, Wenner has considerable experience working on the continent, having benefitted from a Goethe-Institut funded residency in Lagos, in addition to serving as a juror on African film’s biggest awards platform, the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA). ‘’The system by which films are made in Nigeria is very much driven by commercial gains. This is fine and has a right to exist but maybe it is not what we are looking for’’, she explains. So, what is the Berlinale looking for?

A recent example would be Mosese’s MOTHER I AM SUFFOCATING. THIS IS MY LAST FILM ABOUT YOU. A fine fit for the festival’s Forum programme, a segment that encourages risk taking and innovation in filmmaking, Mosese bends the idea of form and structure, using poetic black and white imagery to tell the story of an African’s disillusionment with their home country. It is some strategic filmmaking, blending the personal with the political, but also a film that fits perfectly the European festivals’ expectations of what an African film should be. The better if it comes from a filmmaker exiled in Berlin.

Nollywood filmmakers still struggle with understanding the basic tenets of the (European) festival circuit and as a result often opt out of exploring the considerable opportunities embedded within. Information is helpful; which festival programmes what, and what primary requirements are specific to each festival.

Growing and nurturing a diverse Nigerian cinema palate will take a lot more than relying on the moderately budgeted films that make it to the multiplexes. Individual efforts are important, but the ultimate responsibility of ensuring Nollywood does better at future editions of the Berlinale may depend on the level of interest and support from government. Investment by state institutions in different levels of the filmmaking ecosystem has made all the difference in several countries from Brazil to South Africa. Chile is one of the Berlinale success stories this year. In 2017, the Chilean drama A FANTASTIC WOMAN was the country’s second film to triumph at the Oscars. This year, director Sebastian Lelio is a member of the international jury and about five Chilean films funded at various levels by government institutions are showing in different festival categories. This did not happen by chance. Héctor Oyarzún, a Chilean film critic who has participated in festivals in Berlin and Rotterdam, points out: “It doesn’t happen with the smaller festivals, but for Berlinale there is a government plan. A minister is usually part of the delegation to Berlin and the expenses of everyone involved are taken care of by the public-private sector led Cinema Chile. This institution is responsible for promoting Chilean cinema content and invests a lot of resources in campaigning at big festivals”.

Shaibu Husseini, an alumnus of the Berlinale Talent Press initiative and head of jury at the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA), underlines the importance of government investment in film. “It is expensive getting films to festivals on a regular basis and it isn’t a responsibility only the filmmakers should bear. The specialised agencies, particularly the Nigerian Film Corporation (NFC) and the censors board must be able to identify films fit for festivals and offer all the support needed to get them in”.

After all is said and done, apparently Nollywood must learn to compete globally based on acceptable universal standards. But what are these standards? And are Nollywood filmmakers going to be allowed the privilege of telling their own stories without a predetermined agenda? Wenner sums it up neatly: ‘’The Berlinale has a vast criteria, and sometimes the deciding factor is not if a film is better or worse. The question usually is: is it the right film for us?’’