The viewer launched into doubt

By Felipe Ribeiro

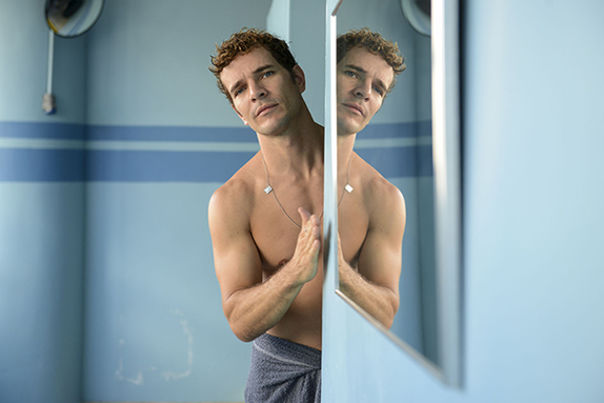

Still from LIQUID TRUTH

With pedophilia as the backdrop, LIQUID TRUTH, by Carolina Jabor, critically analyzes virtual lynching.

To the sound of water and with underwater frames, LIQUID TRUTH invites the viewer, in the first sequence, to dive deep into the plot that is to come. The story revolves around Rubens (Daniel de Oliveira), a children’s swimming instructor accused of pedophilia by Alex (Luiz Felipe Melo), his 7-year-old student.

Alex, despite being at the center of the plot, hardly appears in the film, and almost always in silence. His voice is conveyed solely through his parents' accusation. Anxious for justice, the mother uses the voracious power of social networks to accuse Rubens. The issue of virtual lynching, the pillar of the script, is thus posed. The growing tension is built from the presence of small cell phone screens, which reproduce messages and posts, and the sound work that uses noise to generate restlessness. As the movie progresses, the aggression that began in the virtual world becomes verbal and physical, raising an underlying issue: to take justice into one’s own hands.

Before speaking openly about pedophilia and accusing Rubens of kissing Alex, the first question the father asks about the trainer is whether or not he is a homosexual. There, straight up, the attempt to associate sexual transgressions with the greater freedom in which the LGBTQ community socializes. Carolina Jabor does, however, make a point of not labeling the characters.

The script tries to balance the number of scenes in which the character seems guilty and innocent, as well as Oliveira expressions – which sometimes make him seem guilty, and others make him seem like the victim of an absurd situation. Jabor wants the audience to be in doubt and relies on shots that frame the instructor's small gestures as if with a magnifying glass; some of these images come from the security camera.

Amidst the multiplicity of images and screens that confuse and influence each other, the truth seems to be unreachable. In the open ending, the viewer doesn’t have to choose between guilt and innocence; perhaps he is even instigated to think about how much this need to take sides can be dangerous. It is the kind of film that promotes reflection and debate.